本次講座主要介紹了作爲社會主義遺產和國標準的性別配額在現代中國的發展軌跡。蔣副教授首先介紹了性別配額的采用最早可以追溯到中央蘇區第一次代表大會和陝甘寧邊區第一次代表大會的歷史事實,指出性別配額是被“出口轉内銷”的社會主義的產物。並由此提出了這樣的研究問題:如果性別配額是社會主義的原創產物,那接下來發生了什麽?圍繞著研究問題,蔣副教授説明了性別配額在中央層面和地方層面的複雜現狀和重新采用性別配額的過程與原因。在二十世紀八十年代的人事改革後,婦女參政的人數銳減。全國婦聯注意到了婦女參政的不利情況,進行了許多媒體報導,討論是否應該保證固定比例的婦女參政。時任全國婦聯主席陳慕華利用個人關係向上級部門游説應該保證至少有一名婦女在鄉鎮政府中。在前人基礎上,彭珮雲在1992年婦女權益保障法制定時期提出了性別配額,但沒有被允許通過。她在2000年探訪北歐國家,返程後召開了中國婦女參政研討會,建立了婦聯與學術界的合作。她分別在2001年和2003年向代表大會提交了有關性別配額的草案。總的來説,全國婦聯在性別配額的重新采納中發揮的最重要的作用,游説策略由基於個人關係網的游説轉向為面嚮機構的制度性游説。

Written by: LI, Wenqi

This is a summary of When Socialist Legacy Meets International Norms: Gender Quota Adoption and Institutional Change in China.

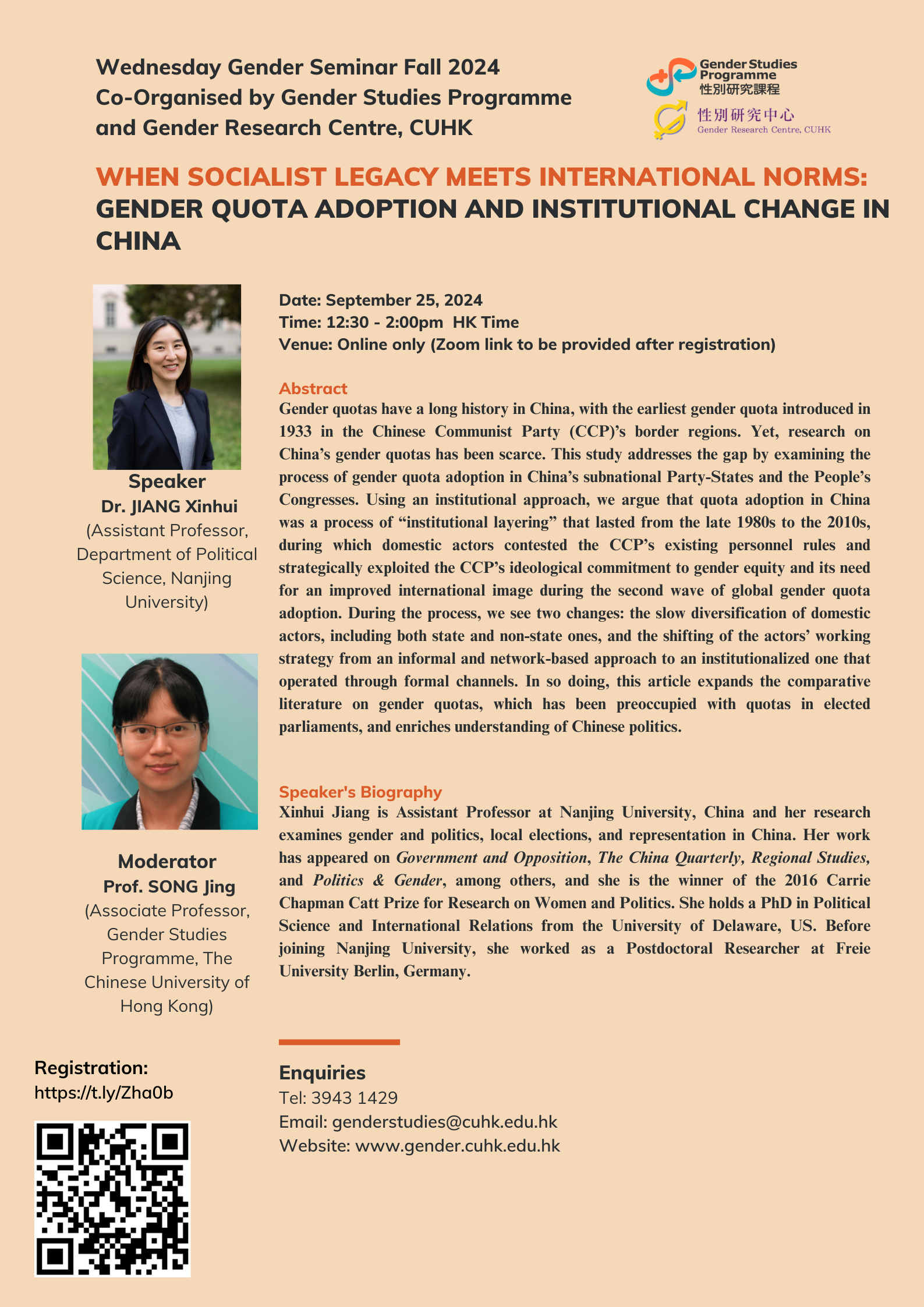

In this lecture, the speaker Dr Jiang explores the process of gender quota adoption in China’s subnational Party-States and People’s Congress. To examine this specific process, which Dr Jiang defines as a process of ‘institutional layering’ from the late 1980s to the 2010s, she takes a feminist institutionalism approach incorporating gender in analyzing both formal and informal institutions and their interactions. In her lecture, Dr Jiang reveals how domestic actors strategically enhanced women’s participation in the electoral rules of the People’s Congresses and the CCP’s personnel management regulations, by exploiting the CCP’s ideological commitment to gender quality and its need for improving international image during the second wave of global gender quota adoption. Domestic actors started from small goals and built on them for the bigger ones, and eventually helped improve women’s political participation significantly by bringing out fundamental policy-changes. Further on, Dr Jiang breaks down the layering process into 3 periods: the 1980s to the early 1990s, the 1990s, and the early 2000s based on the different strategies and changing agents who contest the existing rules. She points out that both strategies and changing agents have evolved during this process: 1) the working strategy of domestic actors has shifted from an informal approach to an institutionalized one that operates through channels like legislative sessions, and 2) the agents who are pushing the policy-changes have expanded from All China Women’s Federation to both non-state and state actors.

This study by Dr Jiang and her colleague fills the gap in existing research, where China’s gender quota was barely touched upon before. It extends the theory on gender quota adoption, showing that a single-party regime is also possible to be influenced by international norms. Meanwhile it identifies various strategies used by changing agents to exert influence upon policy-making process and outcomes. At the end of the lecture, Dr Jiang also talked about how the ‘at least one woman’ quota can be problematic for professional women in bureaucracy in mainland China. Both the ‘at least one woman’ quota and the reserved seats quota have a tendency to produce glass ceiling’ for women’s promotion and raise (unreasonable) doubts about these women’s qualification and capacity.

Written by: WEI, Zerui

This week, Dr. Jiang Xinhui shared her research, When Socialist Legacy Meets International Norms: Gender Quota Adoption and Institutional Change in China. Using a feminist institutionalism approach, she examined why gender quotas were adopted in China and how the process unfolded.

Dr. Jiang traced the origins of gender quotas in China to the socialist policies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In the early 1950s, the Party’s Central Committee issued directives requiring various levels of government to ensure that women should make 15%–20% of the representatives after the Central Soviet Area first implemented the gender quota in 1933. This effort was part of the socialist modernization aimed at encouraging women’s political participation. During the Cultural Revolution, the number of women participating in the People’s Congress increased significantly.

However, affected by economic reforms in the 1980s, class-based political selection rules were replaced with merit- and competence-based criteria, significantly reducing women’s representation in leadership positions. By 1983, women in the Standing Committee dropped from 21% to 9%. In response, Chen Muhua, the chairperson of the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF) lobbied the CCP for expanding gender quotas across all levels of government. The 1995 Beijing World Conference on Women accelerated the push for gender quotas because China was urged to improve its international image on gender equity. State Council institutionalized gender quotas in the Outline for Women’s Development in China (1995–2000). Under the new leadership of Peng Peiyun, the ACWF used research and reports to advocate for more women’s representation. While the suggestion for a one-third gender quota was dismissed in 2005, 26 provinces adopted gender quotas and implemented related programs. The legislative department passed the resolution requiring that the proportion of women should be at least 22% in the 2008 election.

Dr. Jiang concluded that China’s adoption of gender quotas followed an institutional layering model, where new policies built on existing frameworks rather than replacing them. This process was driven by both domestic socialist commitments and international norm diffusion. Nonetheless, the implementation of gender quotas remains limited, with local agencies often interpreting “at least one woman” as “at most one woman.” The intersection of gender quotas with other minority quotas leads to the social stigmatization of female political appointees as ‘token women’ whose appointment fulfills several quota requirements simultaneously.

Written by: ZHENG, Ziwei

A

A

A

Contact Us